Colman Domingo: Finding My Soul at a Greenwich Village Bar

About the author:

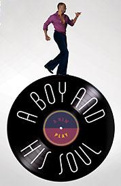

Colman Domingo burst onto the Broadway scene with his charismatic performance in multiple roles (most notably as a morally suspect choir director) in Passing Strange, reprising his work in Spike Lee’s film version of the Tony-winning musical. Domingo has built a varied resume at theaters around the country, particularly in the San Francisco area, and is a regular on the Logo TV series The Big Gay Sketch Show, produced by Rosie O’Donnell. As he shares in this essay, a confluence of events and encounters made him feel compelled to share his personal history as a young African-American in Philadelphia, propelled by the beat of soul, R&B and disco. The resulting solo show, A Boy and His Soul is set to open at off-Broadway’s Vineyard Theatre on September 24. Read on to find out how Domingo found his Soul.

________________________________________________________

In January 2004, I blasted music from my iPod between jazz sets at the legendary 55 Bar in the West Village, where I worked as a bartender. I always had some old-school R&B going. When I would take a break after a full night of service on a Tuesday—I had the worst shifts, by the way—I would put on a mix of Gladys Knight, Phyllis Hyman, Luther Vandross, Donny Hathaway, and so many others, and just breathe. Living the life of a struggling artist in New York City! A drag beauty who stumbled out of the Stonewall Inn with bloodshot eyes leaned against the 55 Bar sign, singing along with the Jacksons from start to finish, “I think about the good times.” She smiled through teary eyes and said, “Thank you, I needed that,” and slid on down Christopher Street.

My belief in the power of this music was valid. It healed and revealed. Between sets and during breaks, I would pull out my notebook and write. Being unflappable in my desire to create. I never thought that this writing would take any shape in the form of a play or a musical or a solo —I hated solo shows. And before I started working on Passing Strange three years ago, I had never considered musicals.

One night, my friend Rodney, a homeless gentleman who would help me clean the bar at 4AM in return for a vodka cranberry and a $5 tip, came in feeling a little down. We’d had many conversations about our lives. He was a former schoolteacher in D.C. He had a bad foot, swollen like a football, and other staff members and I encouraged him to seek medical treatment. Rodney loved the old-school that I would play. I would share with him what was going on with me. Struggling as an artist and trying to help my parents out—they were both suffering from life-threatening illnesses back at home.

On this particular night, Rodney and I didn’t speak much. We were both feeling a little down. We just listened to the music as we cleaned and put the chairs up on the tables. Donny Hathaway’s irreverent song “Someday We’ll All Be Free” came on. At one point I realized that we were both singing quietly to ourselves. I turned the music up. We let the music pour in and out of our souls together. Tears fell from my eyes as I watched Rodney sing out, the veins in his neck about to burst. It was the last song on this “On the Go” mix I made. In the silence we kept on riffing with each other. There was something happening. A change. A shift. My mother always told me that when two or more are in prayer together, you can move mountains! I guess we were praying in this music. We were reaching God together with soul music at the 55 Bar at 4:20AM, trying to heal our hearts.

For months after that moment I didn’t seen Rodney. It was a cold winter, and I thought that the unfortunate had befallen my early morning friend. In the spring I was working on and off in between acting jobs. Susie, the Irish lass of a bartender, told me that Rodney had stopped by to say hello and I missed him. She told him when I would be working, and he said he would stop in. When I started my shift at about 9PM, I went outside to write the upcoming band on the blackboard by the door. Who was sitting out there, beaming in a wheelchair? You guessed it!

Rodney looked great! He was in clean clothes and his hair was trimmed. He looked like a teacher! He told me his foot had had to be to cut off, and that is why he was in the wheelchair. He went through a rehab and was off of drugs. He was going to go home to D.C. and stay with his mother for a bit. He smiled with such pride. His gravelly voice was less raspy. I was proud of him. He said, “Thank you, Colman, you are a good friend.” And that was the last time I saw him.

When the bar cleared out, I put on my music and wrote. I think that my new solo show, A Boy and His Soul, got its inspiration from the catharsis I witnessed. In the back of my mind I always believed that Donny Hathaway helped Rodney get to where he needed to get in that moment. At the same time, my parents put our family house up for sale, leaving behind crates and crates of music. I held a reverence to this music. This archive of our lives. I wanted to examine it. Hold it up to the light and wonder where it would carry me. This was a solo journey. This play became the journey of a boy from West Philadelphia, raised in one of the great eras of soul music, searching through the archives of his home and the beat of his heart…in the music.